How to Identify Fake Antiques

August 2nd, 2012 by adminAs antiques aficionados, most of us appreciate authenticity and are drawn to items that have provenance or –at the very least– are as old as they are purported to be by the person trying to sell them. But now and then an item may be sold under a false pretext, and it can save us money and heartbreak if we recognize this before bringing it home.

“Fake” versus “Not Very Old”

There are two ways one may be led into buying an antique with a lower value than advertised. One is the circulation of an actual “fake”, a counterfeit “Tiffany” lamp, “Chippendale” chair, or “1923 Rolex” watch, for example. These kinds of fakes (except for the watch– more on that later) are actually very difficult to create and pass off as the real deal. It takes an intense degree of craftsmanship and attention to detail to pull off a scheme like this, especially when it comes to wooden furniture, so you don’t see these kinds of things very often. All the same, here are a few tips to keep in mind:

- Some deals are too good to be true. If the price of an item seems way too low, feel free to buy it, but don’t count on being able to resell it as an authentic piece.

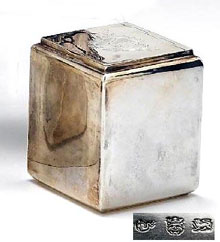

- If you’re trusting a label or watermark to tell the truth, it’s best to have some experience with that particular maker so you know exactly what the correct version looks like. Joining collectors clubs or similar social groups can expose you to experts and help build your knowledge and confidence.

- Sometimes pottery and ceramics have minor defects and are sold as “factory seconds.” In this case, the maker will often strike out the signature. If you believe you’re looking at a factory second, buy at your own risk. The manufacturer has disowned the item, and you can’t prove the authenticity of the piece when you sell it, but you may still find pleasure in owning it.

“Not Very Old”

Some misleading items are simply recently-made pieces that are passed off as old. An item sold as a colonial table or an 18th century German cuckoo clock may have been made in a factory last week. Here are a few ways to tell.

- Over time, wood changes shape along the grain. The length stays the same, but the width varies. If a round table is still perfectly round, it may not be very old. Square shelves that fit imperfectly in cabinetry, gaps, slight buckling, and a general misshape are all good signs.

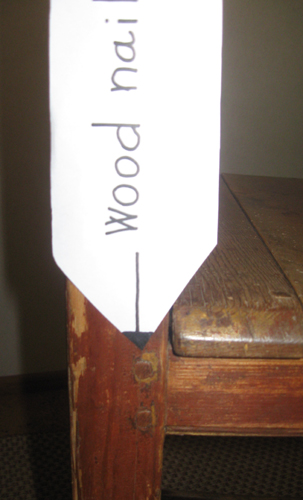

- Check the woodworm holes and the joining pegs. Tiny cracks should not radiate from the wormholes, and the joining pegs should stand out slightly from the surrounding wood as it shrinks back with time.

- Dovetail joints should be a bit rough. Uniform cuts suggest a 20th century factory. Rougher, uneven cuts suggest handwork.

- Check patterns of grime and wear. The piece should show more distress in the places where it’s been touched most over the years, like on the arms of chairs and the handles of things. Uniform wear is a bad sign.

- Read the description carefully. Items sold as “in the style of” or “inspired by” are not claiming to be antique. These are perfectly legal and legitimate imitations of antique items.

A Few Additional Tips

Remember that “authentic” can be a purely philosophical distinction. Antique items have been popular for thousands of years. “Fake” antique tables were bought and sold during biblical times. If you come across one of these, I’d hold onto it.

By the same token, if a wooden table is made from the boards of an old barn, is it old? As the buyer, you are allowed to decide. But it’s harder to dictate these terms when you become the seller.

When an item becomes appealing to speculators, fakes abound. Show caution when buying something at the peak of popularity.

Use your nose. Real silver has a very distinctive smell. So does old wood in the enclosed space of a drawer or cabinet.

Repair and patchwork are also subjective matters, but they diminish official resale value. Be especially cautious of patchwork when it comes to items with many small parts, like watches and clocks. One modern replacement spring mechanism may render a watch inauthentic, and may be very difficult for non-experts to detect.

By Erin Sweeney

for Antiques.com

Every collector has occasion to wonder if the item they just got a great deal on is the real thing or a clever fake. Face it, as much as we all love a bargain, we’re haunted by the ‘too good to be true’ motto. Much of this fear can be alleviated if you buy a book or two about your chosen collectible, and if you keep up with what’s going on in the market – Collector organizations work very hard to maintain databases of the fakes that are out there.

Every collector has occasion to wonder if the item they just got a great deal on is the real thing or a clever fake. Face it, as much as we all love a bargain, we’re haunted by the ‘too good to be true’ motto. Much of this fear can be alleviated if you buy a book or two about your chosen collectible, and if you keep up with what’s going on in the market – Collector organizations work very hard to maintain databases of the fakes that are out there. Fake…a word no collector or dealer ever wants to hear. Fakes run rampant in the antiques and collectibles industry. Many people think fakes are only for expensive items such as Monet paintings, diamond jewelry, and Rolex watches. Not so!

Fake…a word no collector or dealer ever wants to hear. Fakes run rampant in the antiques and collectibles industry. Many people think fakes are only for expensive items such as Monet paintings, diamond jewelry, and Rolex watches. Not so!